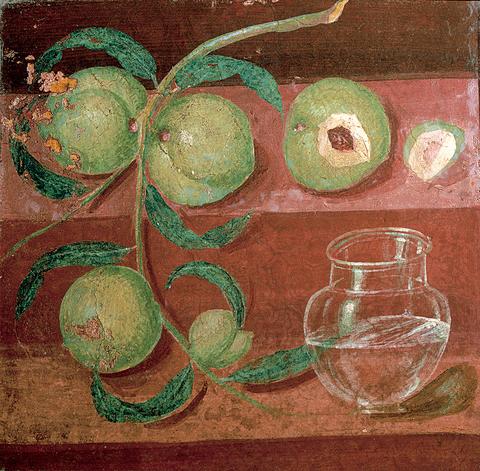

Still Life with Peaches, ca. 50A.D., from the ancient Roman town of Herculaneum, courtesy of the Archaeology Museum, Naples

There is a cloud hanging over Tate Modern. Or, more precisely, hanging next to it. It’s a flinty, overcast April day and, as I walk through Fujiko Nakaya’s fog ‘sculpture’ beside the Thames, I lose my sense of where the sky begins. The air is cool and damp and tastes a little sweet, like the steam in the bathroom after you’ve had a shower. Nakaya has been working with fog as a sculptural medium since 1970, when she shrouded the hard origami-inspired angles of the Pepsi Pavilion at Osaka’s Expo ’70 in cloud. Sometimes the mists last a couple of hours, sometimes a few days. Some are recreated daily, as in the sculpture garden at the National Gallery of Australia, where a fog piece forms part of the permanent collection. The date of that work is given as 1976, whatever that means. Each of Nakaya’s sculptures is the same but different; insofar as fog has no form proper, it might be best considered as a means — literally and metaphorically — of momentarily seeing other things differently. It’s a question of fallibility, of misrecognition, of humanity (for which also read mortality). Fog renders our grip on things less secure; it’s the blank endpoint of a kind of psychological entropy: the whiteout to which memories and dreams bleach as they fade. (Nakaya’s father, Ukchiro, spent a lifetime photographing and classifying snowflakes; he created the first artificial snow crystal in 1936 — both preoccupations as if in defiance of snow’s fleetingness.)

“However solid objects seem, yet they are formed of matter mixed with void,” wrote the Roman Lucretius in the first century BCE. “In rocks and caves the watery moisture seeps, and beady drops stand out like plenteous tears.” His poem De Rerum Natura (On the Nature of Things) is a book that wrests fear and wonder away from the gods and back into the world of things. In essence, it has to do with living life in the full consciousness of death, which could also be rephrased as: life, in part, is the full consciousness of death.

I read a story recently about Calico, a company set up by Google with a billion dollars worth of funding, whose aim is to find a way of extending life indefinitely. Death isn’t ‘curable’: it’s the fundamental horizon against which our sense of self, our consciousness, our desires, evolve. Did we abandon the gods only to recreate ourselves (or at least the very privileged few) in their image?

On the cover of my copy of De Rerum Natura is a detail from a mural uncovered at Herculaneum. The painting is known — somewhat anachronistically, given that the genre was born on the cold tables of Northern Europe in the 16th century — as Still Life with Peaches. The peaches are an unripe green. They look tart and unyielding, exercises in form rather than sensory provocation. From one, a little diamond-shaped cross-section has been excised, revealing the dark hole of the stone. “Horror vacui” said Aristotle. Nature abhors a vacuum. To which Lucretius countered that as one void is filled, another one is formed.

The picture reminds me of a painting by Mary Fedden from the mid-1950s of herself and her husband, Julian Trevelyan, in their kitchen at Durham Wharf in Chiswick. Lying on the table in the foreground is a pair of swollen, oversized pears with waxy yellow skin. They have been sliced not quite in half and six black seeds fill the belly of each. The lamp glows, the man chops, the shelves in the foreground are stacked with fruits and vegetables. I’ll perhaps never see that painting again: it hangs in the kitchen of an ex’s father’s house. A reminder that, however solid things might seem, nothing lasts forever.