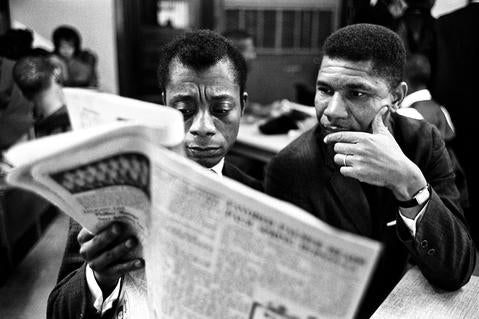

James Baldwin and Medgar Evers, 1963, photo courtesy of Steve Schapiro ©Steve Schapiro

It is exactly the uneasy imaginary of becoming American that novelist and essayist James Baldwin took up in his 1959 meditation, “The Discovery of What It Means to Be an American.” Baldwin opens with the words of compatriot and self-exiled novelist Henry James; a direct salvo toward any fixed definition of American identity: “It is a complex fate to be an American.” That Henry James himself took the extraordinary final step of becoming a British citizen in the last year of his life, 1915, attests to the questioning and differential urge that spurred James’s uneasy body of work, and his decided refusal to take part in American civic life. Aside from two short trips to the United States, James spent the final three decades of his life in Europe, effectively relegating his American experience to the rearview, grist for fictional context and back story. Baldwin rips James’s phrase into the present in order to challenge and pivot his own “direct relations” with becoming American and what that “Discovery” might mean as he moved forward as a writer: “That the tensions of American life, as well as the possibilities, are tremendous is certainly not even a question. But these are dealt with in contemporary literature mainly compulsively; that is, the book is more likely to be a symptom of our tension than an examination of it. The time has come, God knows, for us to free ourselves of the myth of America and try to find out what is really happening here.” Baldwin’s choice was to exist both inside and outside of American experience, shuttling between Europe and the U.S. as a way of life, a native son striving continually to become more American through a self-examination precipitated, and enabled, by distance.

As a self-appointed ambassador speaking truth to power, Baldwin entered into the fray of the burgeoning Civil Rights movement through essays and journalistic assignments. Still, he maintained the literal distance of Europe for the writing of his novels, cultivating his position as an outsider through his fiction. Embedded in the titles of Baldwin’s writing, this permanent, never-to-be-resolved tension proved generative — a declarative stance regularly flips to a more ruminative and isolated one: Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953), The Amen Corner (1954), and The Fire Next Time (1963) parry with Stranger in the Village (1953), Giovanni’s Room(1956), and Nobody Knows My Name (1961). Nevertheless, his work as a journalist would lead him to the center of the civil rights movement, especially through his coverage of the sit-in movement in Tallahassee, Florida in 1960, which introduced him to members of CORE (the Congress of Racial Equality) and resulted in an U.S. lecture tour under their auspices in 1963. Baldwin became an increasingly high profile speaker, his network extending rapidly to the NAACP, including his friendship with Medgar Evers (the NAACP’s Mississippi field secretary), and provided him access to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X, among others. Baldwin carved out a unique position as both a participant in, and observer of, the socio-political sea change that was then transforming public life in America.

Baldwin’s need to work against injustice and advocate for change within civic life was complicated by an earlier resolution to accept people as they were — racial prejudices included — in order to understand others more deeply as a novelist. As he wrote in an early essay, “Notes of a Native Son” (1955), the charge he gave himself was to maintain a demanding, even harrowing harmony: “It began to seem that one would have to hold in the mind forever two ideas which seemed to be in opposition. The first idea was acceptance, totally without rancor, of life as it is, and men as they are: in the light of this idea, it goes without saying that injustice is a commonplace. But this did not mean that one could be complacent, for the second was the idea of equal power: that one must never, in one’s life, accept these injustices as commonplace but must fight them with all one’s strength.” Indeed, Baldwin inhabited and transposed scenes from his own experience with considerable empathy and understanding of loss, vividly animating the Harlem of his childhood and young adulthood in novels like Go Tell It on the Mountain or in the devastating helplessness of the short story Sonny’s Blues (1957). And yet Baldwin, the hyper-sensitive novelist now mining his life in Harlem, also began to assume the role of public ambassador — fiercely articulate, knowingly complex in his views on race and racism in America, and yet ready to talk.

The very acuity that brought him to the center of civic turmoil and activism (including his appearance on the cover of TIME magazine in 1963 next to the headline “Birmingham and Beyond: The Negro’s Push for Equality”) further revealed the tension inherent within his own aesthetics and ethics, a stance that frustrated and disappointed many. For example, in a private meeting with Attorney General Robert Kennedy in 1963 — arranged in part due to Baldwin’s public assertion that John F. Kennedy’s inaction directly contributed to the violent assault of peaceful Civil Rights protestors by police in Birmingham, Alabama — Baldwin supposedly suggested that black Americans couldn’t and shouldn’t be relied upon to fight in Vietnam given the pervasive state of racial injustice and inequality domestically. Dismissed by Kennedy as intractable and divisively unpatriotic, Baldwin was simultaneously criticized by Eldridge Cleaver and other radical black activists for a perceived sycophantic relationship to power that attempted to curry proximity and favor rather than actively resist.

Ultimately, Baldwin’s embrace of seemingly opposing stances in regards to racism rendered him an outsider on the inside of a culturally defining moment. It is this inclination toward confronting the bifurcated self that gives Baldwin’s work such resonance today. In the introductory note to his essay collection Nobody Knows My Name, Baldwin linked his desire to be free as an artist to his resolution to continually confront himself: “The questions which one asks oneself begin, at last, to illuminate the world, and become one’s key to the experience of others. One can only face in others what one can face in oneself. On this confrontation depends the measure of our wisdom and compassion.” The phrase “begin at last” betrays Baldwin’s difficulty in arriving where he did as a writer, innovative in both fiction and prose. And yet Baldwin’s capacity to rehearse, analyze, and deconstruct the ideologies and barriers of race, gender, and identity politics as a public figure was equally pioneering.

That Baldwin lent both permanence and illumination to his framing of confrontation (confrontation does not resolve but is countered with a measure of compassion) calls to mind the words and work of visual artist and writer Adrian Piper. Reflecting on her series of photographs, writing, drawings, and street performances, The Mythic Being (1972 – 75), in a 1981 essay, Ideology, Confrontation, and Political Self-Awareness, Piper emphasized the importance of an aesthetics of self-confrontation. Her words resonate with Baldwin’s own charge that: “Doubt entails self-examination because a check on the plausibility of your beliefs and attitudes is a check on the constituents of the self.” Piper’s alter ego in the Mythic Being series dons an afro wig, aviator sunglasses, a fake mustache, and an ever-present cigarette to perform various scenes of mock aggression, intimidation, and confrontation, often in public settings. Creating a masquerade of stereotypes ascribed to black masculinity, Piper’s photo-based series adopts conceptual art procedures (including staged photography and the circulation of work via paid-for-print advertising in the Village Voice) to document her own freighted responses and those of others. To create the menace of the Mythic Being, Piper mined her own journal writings of the decade prior from the series The Mythic Being; I / You (Her), 1974, in which Piper’s metamorphosis into the Mythic Being is visualized in a sequence of photos captioned with speech bubbles detailing the deterioration of a lover’s relationship. Having begun the series when she was a doctoral student in the Philosophy Department at Harvard University, the Mythic Being was an exploration of self-estrangement — Piper adopted the transformation theme in part as a response to her experience of frequently being mistaken for white though she was the only woman and black student in her department.

As Piper has written of her work more broadly, “I try to construct a concrete, immediate and personal relationship between me and the viewer that locates us within the network of political cause and effect.” With The Mythic Being, the serial procedures of conceptual art do just that. An excerpt from Peter Kennedy’s film, Other Than Art’s Sake (1973 – 74), offers a behind-the-scenes encounter with Piper getting into character, a non-artwork that in Piper’s own words is “a hilarious documentation and interview on my Mythic Being street performances. It shows me getting into and out of drag, rehearsing my mantra, and roaming the streets muttering it, followed by the curious onlookers who are attracted by Peter’s film equipment and technicians.” Ending with a walk through the streets of Manhattan’s Lower East Side, the video captures Piper’s transformation into the Mythic Being, a trance-like presence parting the gathering crowds.

While clearly parodic, the series as a whole addresses the politics of race, gender, and identity as issues needing to be rehearsed in order to reveal — and not merely perpetuate — the unexamined. Reflecting on the impetus for the work, Piper echoes Baldwin’s call to confront internally what is encountered externally: “We started out with beliefs about the world and our place in it that we didn’t ask for and didn’t question. Only later, when those beliefs were attacked by new experiences that didn’t conform to them, did we begin to doubt: e.g., do we and our friends really understand each other? Do we really have nothing in common with blacks / whites / gays / workers / the middle class / other women / other men / etc.?” With Piper’s first full retrospective opening in 2018, we have the opportunity to learn more deeply from the aesthetics of confrontation that animate her work. And, with our empathic cultural ethics now under greater threat than ever before, it is also an opportunity to return to the breadth of James Baldwin’s oeuvre. Perhaps in doing so, we might understand more fully what it means to become American, in reaching for the measure of our compassion.